Doughnut Economics and AI

A New Future for AI: Eight Shifts to Enable Regenerative and Distributive Transformation

Beyond the Default Mode

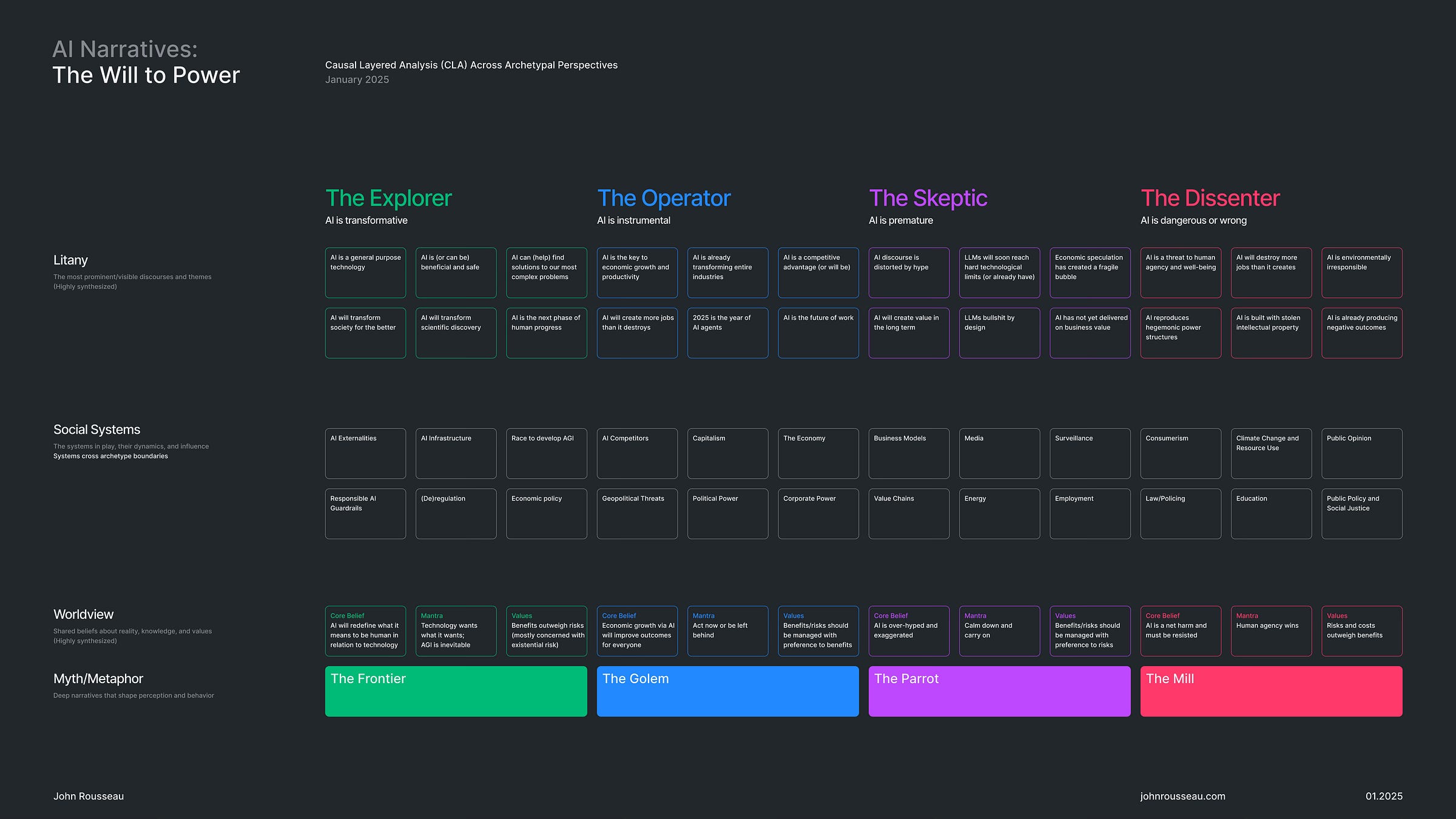

Previously, I wrote about AI archetypes—four distinct worldviews that see the present and future of artificial intelligence differently. I used Causal Layered Analysis (CLA) as a way to highlight divergent perspectives and argued that the future of AI is dependent on a synthesis and/or transformation of these narratives—inclusive of the systems that undergird them.

I concluded that piece with:

For AI, there is a clear need to evolve our theories of change and develop alternative images of the future that challenge the status quo and reconcile competing narratives. Then, perhaps it would be possible to move beyond passive, default-mode thinking and exercise our collective agency to create something new.

Here, I want to pick up the thread and take the next step. That involves imagining alternative structures and values at the systems level, and considering the implications for AI.

But first, I want to talk about the default mode.

I often return to this quote by David Foster-Wallace from This is Water, his Kenyon College commencement address:

The really important kind of freedom involves attention and awareness and discipline, and being able truly to care about other people and to sacrifice for them over and over in myriad petty, unsexy ways every day.

That is real freedom. That is being educated, and understanding how to think. The alternative is unconsciousness, the default setting, the rat race, the constant gnawing sense of having had, and lost, some infinite thing. (Wallace, 2005)

The rat race (1). Default-mode futures emerge from the same power structures and discourses that shape our day-to-day awareness—what Foucault called the episteme. Our images of the future reflect the constraints of our worldview, our expectations and experience, and the context of our social systems, whether we are conscious of it or not (2).

So, when Wallace says that being educated is understanding how to think, he means that we need to cultivate empathy and practice critical awareness. That’s also a function of foresight—the deliberate deconstruction of knowledge about the future, and a call to new futures that challenge the default mode and create affordances for human agency in the present.

Toward New Futures

In my previous narrative analysis, I suggested that relative to AI, the structures of capitalism (at the systems level) were inextricable from the litany (above) and the worldviews (below). The default future of AI is largely driven by the dominant archetypes—a worrisome blend of determinism, creative destruction, and technofeudalism.

The four archetypes and their core beliefs are:

The Explorer: AI will redefine what it means to be human in relation to technology

The Operator: Economic growth via AI will improve outcomes for everyone

The Skeptic: AI is over-hyped and exaggerated

The Dissenter: AI is a net harm and must be resisted

One could argue that the structures of the system emerge from these worldviews, or that it goes the other way, or that it goes both ways, which seems most likely. In a complex system, it is impossible to identify precise causal relationships—so I want to focus on the implications of changing the goals of the system and its constraints, which could be accomplished in various ways (e.g., via collective action, policy interventions, market forces, etc.).

Any useful image of the future should appear to be ridiculous. But not all ridiculous ideas are useful. (Dator, 2006)

Right now, I’m not concerned about tactics as much as the provocation that systemic change would drive radically different outcomes for AI. A new image of the future that may at first appear ridiculous depending on the extent to which you think the current economic system is working just fine or is intractable or otherwise unchangeable. If that’s the case, document the assumptions you are making, the constraints you take for granted, and your overall theory of social change. This is your personal default mode—you can always return to these ideas later.

What would be a useful image of the future? Useful doesn’t mean likely—only that we can envision a plausible alternative that might inform action in the present. Being open to new or even seemingly ridiculous thought experiments helps us expand our awareness and reframe our thinking, which in turn shapes what is possible.

Shifting Paradigms

Changing the goal of the system is the foundational premise behind Doughnut Economics—a framework introduced in 2011 by economist Kate Raworth and later elaborated in Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. Raworth argues that the goal of GDP growth should be replaced by measures that create a dynamic balance between social and planetary health. (Raworth, 2017)

She writes:

What exactly is the Doughnut? Put simply, it’s a radically new compass for guiding humanity this century. And it points towards a future that can provide for every person’s needs while safeguarding the living world on which we all depend. Below the Doughnut’s social foundation lie shortfalls in human well-being, faced by those who lack life’s essentials such as food, education and housing. Beyond the ecological ceiling lies an overshoot of pressure on Earth’s living systems, such as climate change, ocean acidification and chemical pollution. But between these two sets of boundaries lies a sweet spot—shaped unmistakably like a doughnut—that is both an ecologically safe and socially just space for humanity. The twenty-first-century task is an unprecedented one: to bring all of humanity into that safe and just space. (Raworth, 2017)

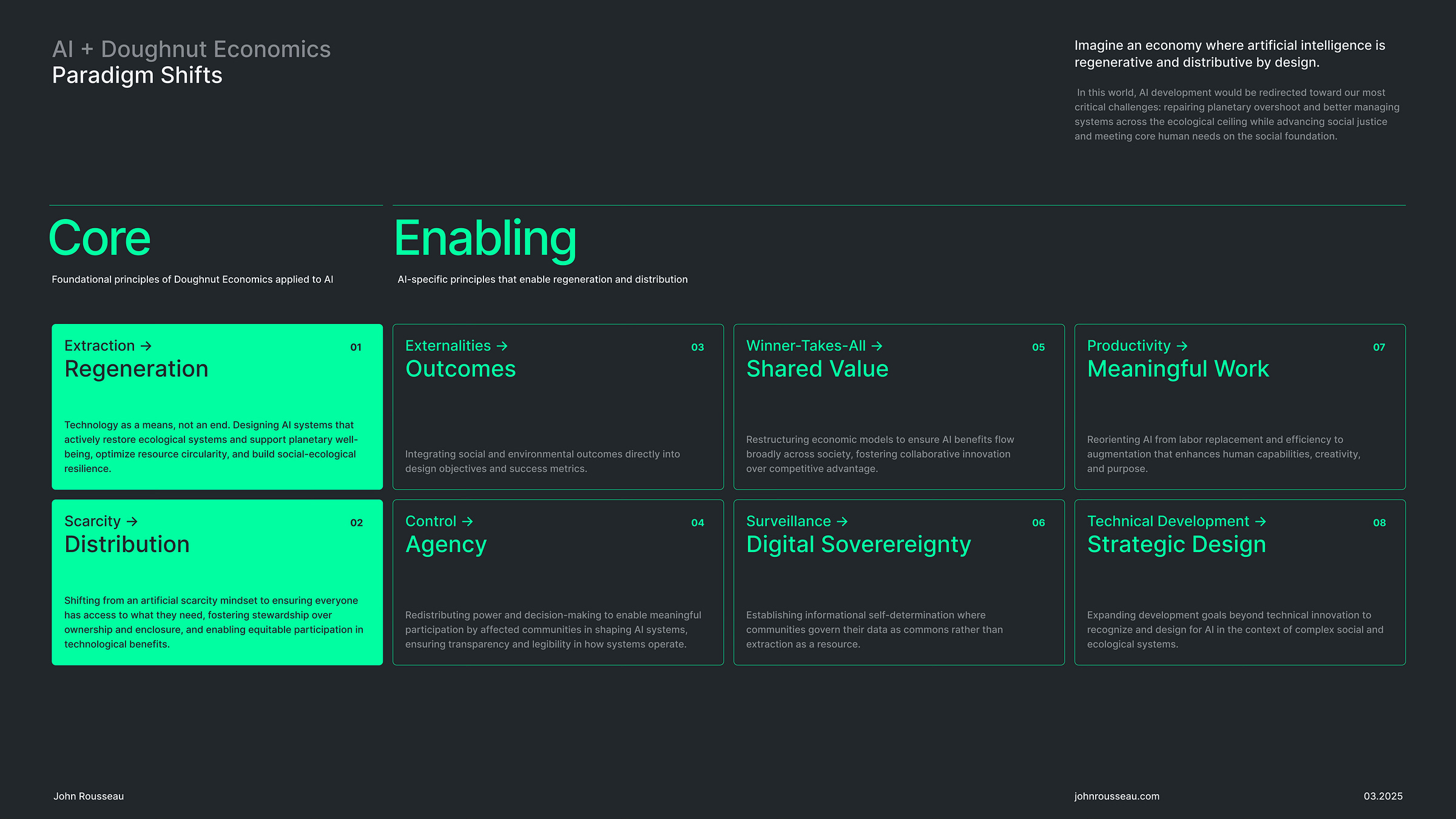

Imagine an economy where artificial intelligence is aligned with doughnut economics principles—where AI is regenerative and distributive by design. In this world, AI development would be redirected toward our most critical challenges: repairing planetary overshoot and better managing systems across the ecological ceiling while advancing social justice and meeting core human needs on the social foundation.

Rather than optimizing for economic growth or material dominance, AI would be developed to help humanity thrive within the "safe and just space" between social and planetary boundaries—which requires fundamental changes in how we design, deploy, and govern the technology. Here are eight ways that could happen, as part of a holistic approach to systems change.

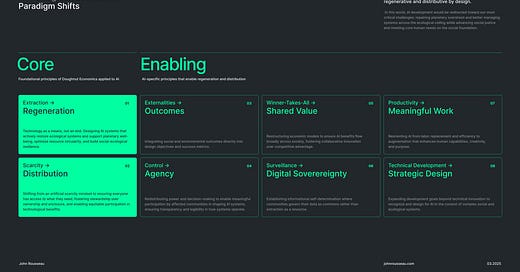

Core Shifts

Extraction → Regeneration: Technology as a means, not an end. Designing AI systems that actively restore ecological systems and support planetary well-being, optimize resource circularity, and build social-ecological resilience.

Scarcity → Distribution: Shifting from an artificial scarcity mindset to ensuring everyone has access to what they need, fostering stewardship over ownership and enclosure, and enabling equitable participation in technological benefits.

Enabling Shifts

Externalities → Outcomes: Integrating social and environmental outcomes directly into design objectives and success metrics.

Control → Agency: Redistributing power and decision-making to enable meaningful participation by affected communities in shaping AI systems, ensuring transparency and legibility in how systems operate.

Winner-Takes-All → Shared Value: Restructuring economic models to ensure AI benefits flow broadly across society, fostering collaborative innovation over competitive advantage.

Surveillance → Digital Sovereignty: Establishing informational self-determination where communities govern their data as commons rather than extraction as a resource.

Productivity → Meaningful Work: Reorienting AI from labor replacement and efficiency to augmentation that enhances human capabilities, creativity, and purpose.

Technical Development → Strategic Design: Expanding development goals beyond technical innovation to recognize and design for AI in the context of complex social and ecological systems.

A New Future for AI

Following these paradigm shifts, I imagine a transformative future in two stages of development, summarized as follows (3, 4).

Horizon Two: Transition (2035-2040)

This is a transitional period following strong catalysts for change, including increasingly catastrophic climate events, downstream impacts of biodiversity loss, geopolitical conflict, social instability, and economic disruptions—all creating the conditions for governments, businesses, and society to recognize the need for alternatives and pursue actions aligned to Doughnut Economics and the eight strategic shifts. A new world is emerging—where AI is radically redirected and realigned to a common purpose and clear priorities.

Even so, progress is uneven and previous inaction on climate and inequality has created a fragile and turbulent global context. Capital initially resists these shifts, while bad actors create chaos. Regulatory frameworks are slow to adapt and struggle to balance innovation with emerging social and ecological imperatives, creating uneven impacts. Exemplary changes include:

Alignment of AI to ecosystem boundaries and directed at circular/regenerative outcomes, such as tracking biodiversity, predicting and mitigating climate events like wildfires, or restoring marine ecosystems.

Carbon-aware management of compute resources. AI systems optimize the distribution and storage of renewable energy, balancing supply and demand across smart grids, directing resources, and optimizing energy consumption.

24-hour work week for many, inclusive of subsidized income and education, while greater value is placed on care work, creativity, and community.

Holistic well-being metrics begin to augment/replace GDP, with a growing emphasis on measures of social and ecological health, leading to policies and investments that prioritize these goals.

Commons-based governance of AI infrastructure, open-source models, policy, and data, characterized by transparency and community decision-making.

Horizon Three: Transformation (2050+)

A new system has emerged and matured following the disruption of the previous decades, with fully regenerative and distributive economics having replaced the extractive system. This required significant changes to both systemic structures and worldviews, which are broadly aligned with foundational requirements for a just and sustainable world. Collective flourishing for both people, other species, and the planet is seen as the primary measure of societal success, and a “deep time” perspective is integrated in decision-making processes. Exemplary changes include:

AI as an orchestrator of regenerative and circular product flows and enabling value chains, accompanied by a shift in consumption behaviors and culture.

Distribution of AI benefits as a public good, accompanied by a reduction in global inequality. Most people are now “in the doughnut,” with corresponding shifts in equitable access to health, education, and economic participation.

Integrated global governance of AI systems and collective sense-making and political participation, aligned to shared goals and values.

Emergence of bioregions as a form of ecological and social governance, supported by AI systems that enable community engagement and regenerative management of key resources.

New paradigms for work and human flourishing that are not based on the exploitation of labor or the exchange of time for money, and that facilitate the emergence of new, more sustainable forms of production and consumption.

Endnote

Is a regenerative and distributive image of the future for AI ridiculous? Considering present conditions, it may come across as either utopian or implausible.

The transition faces significant headwinds: entrenched economic interests, technological path dependencies, and social resistance. Political dysfunction and short-term thinking further complicate collective action. Yet these barriers also highlight leverage points where targeted interventions could catalyze positive change.

It’s important to recognize that even within current constraints, there may be useful applications of the eight paradigm shifts, assuming alignment regarding the underlying goals of Doughnut Economics. We could begin to integrate these principles into AI development today, for example, by allocating resources to AI systems that focus on circular or regenerative solutions, or that are more clearly aimed at human flourishing. AI safety and ethics could also be expanded to include these perspectives and drive new forms of accountability.

Different stakeholders have a responsibility to advance these shifts from their unique positions: researchers by reorienting AI goals, companies by adopting regenerative business models, policymakers by creating enabling conditions, and communities by asserting their right to shape technologies that affect them.

Beyond this, it's crucial to recognize that we needn't accept the default future or underlying systems as fixed. Systemic change—while challenging—would open up radically different possibilities for AI and for the future of our society and planet. Envisioning alternative futures and adopting a critical perspective are crucial for challenging the status quo, clarifying our values, and expanding our sense of what's possible.

The goal is not just to develop better AI, but to create a future where AI empowers humanity to thrive within an authentically safe and just ecology. Beyond that, I would leave open the possibility for a novel synthesis to emerge, one that transcends the default mode of the present and enables a transition to a truly preferable future.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider a one-time or monthly donation to support my independent design, writing, and research.

Notes

I appreciate Wallace’s turn of phrase, how he follows “rat race” with “gnawing sense…”. It’s a clever juxtaposition, gnawing as a metaphoric hunger for what has been lost and, well, rats. The etymology of “rat race” is interestingly vague—the modern connotation first appearing in 1939 and becoming mainstream in the 1950s. The term is possibly linked to actual rat races that were prevalent in carnivals and gambling attractions in the 1930s, and/or an early aviation training activity (otherwise called “follow the leader”). Also: Happiness

Futurist Sohail Inayatullah refers to a similar concept as the “used future,” by which he means the unthinking adoption of hegemonic images of the future.Giving the example of Western economic growth, he writes: “Asian cities have unconsciously followed this pattern. They have forgotten their own traditions where village life and community were central, where living with nature was important. Now they must find ways to create new futures, or continue to go along with the future being discarded elsewhere. This used future is leading to a global crisis of fresh water depletion, climate change, not to mention human dignity.” (Inayatullah, 2008). I prefer the term “default mode” because it suggests the issue is more a failure of conscious awareness than origin (we all have defaults, regardless of where they come from), and that it can be overcome by opening and reframing our thinking during the foresight process.

Note that these are not fully-developed or comprehensive scenarios.

For an explanation of the Three Horizons framework, please see my previous piece on the Future of Work.

References

Dator, J. (2006). "Any useful idea about the future should appear to be ridiculous." In Next Generation Exploration Conference 2006 (p. 42). NASA. Retrieved from https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20070008272/downloads/20070008272.pdf

Foster., Wallace, D. (2009). This is water : some thoughts, delivered on a significant occasion about living a compassionate life. Kenyon College. (1st ed.). New York: Little, Brown.

Inayatullah, S. "Six pillars: futures thinking for transforming." Foresight VOL. 10 NO. 1 (2008).

Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. Random House Business.