The Issue

I was recently asked about the future of design. My answer was that design is a transdisciplinary field adapted to addressing issues in complex systems—both as a convener of other disciplines and via its own unique disposition and evolving toolkit.

My interlocutor pointed out that there are many futures of design (indeed), and expressed skepticism about the market for my definition. Fair enough.

Later, I realized that I answered a different question than what was asked—namely, by sharing my preferred future of design rather than the most likely scenario, the scenario most aligned with the current system, or the scenario with the most economic upside.

I also made a tacit assumption about the meaning of “design,” which I view less in terms of disciplinary boundaries and more in terms of an overarching ethos and set of values.

So it goes.

Why it Matters

Design appears to be in a state of decline or stagnation, particularly in terms of human-centered design (the context of my prior conversation), digital product design, and adjacent disciplines. Extraordinary growth over the past two decades has reversed amidst shifting business priorities, an oversupply of practitioners relative to demand, greater efficiencies, commodification, and emerging forms of automation, among other reasons.

Meanwhile, the downstream effects of design are profound, from “brain rot” to planetary boundary crossings and the Polycrisis.

In the preface to Design for the Real World, Victor Papanek begins:

“There are professions more harmful than industrial design, but only a very few of them.”

And concludes,

“As socially and morally involved designers, we must address ourselves to the needs of a world with its back to the wall, while the hands of the clock point perpetually to one minute before twelve.” (Papanek, 1971)

The Dominant Narrative

A common explanation for the downturn is that design failed to deliver sufficient business value, and/or failed to fully integrate design within the organization.

This, despite years of effort.

Here’s McKinsey giving it the full treatment in 2018:

The Business Value of Design (2018). There’s a diamond in there! You can feel the value waiting to be unlocked.

Implicit in this narrative is the idea that business value is a prima facie good above all else, and that the purpose of design is to amplify business growth—a goal that is measured by correlating design maturity with financial outcomes.

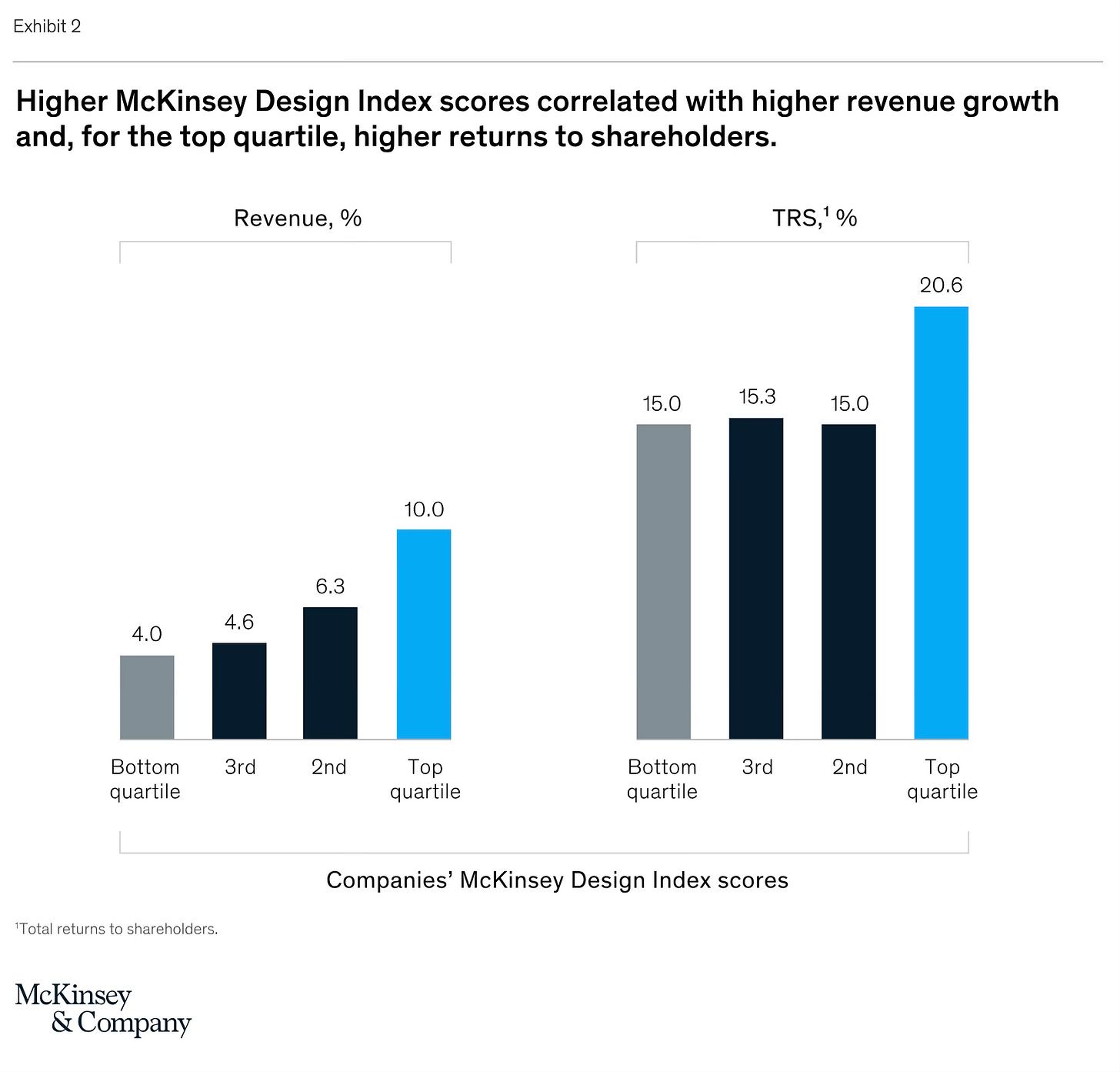

Again, McKinsey:

Continuing, they write:

The companies in our index that performed best financially understood that design is a top-management issue, and assessed their design performance with the same rigor they used to track revenues and costs. In many other businesses, though, design leaders say they are treated as second-class citizens.

Design issues remain stuck in middle management, rarely rising to the C-suite. When they do, senior executives make decisions on gut feel rather than concrete evidence.

Designers themselves have been partly to blame in the past: they have not always embraced design metrics or actively shown management how their designs tie to meeting business goals. What our survey unambiguously shows, however, is that the companies with the best financial returns have combined design and business leadership through a bold, design-centric vision clearly embedded in the deliberations of their top teams. (McKinsey, 2018)

An Emerging Narrative

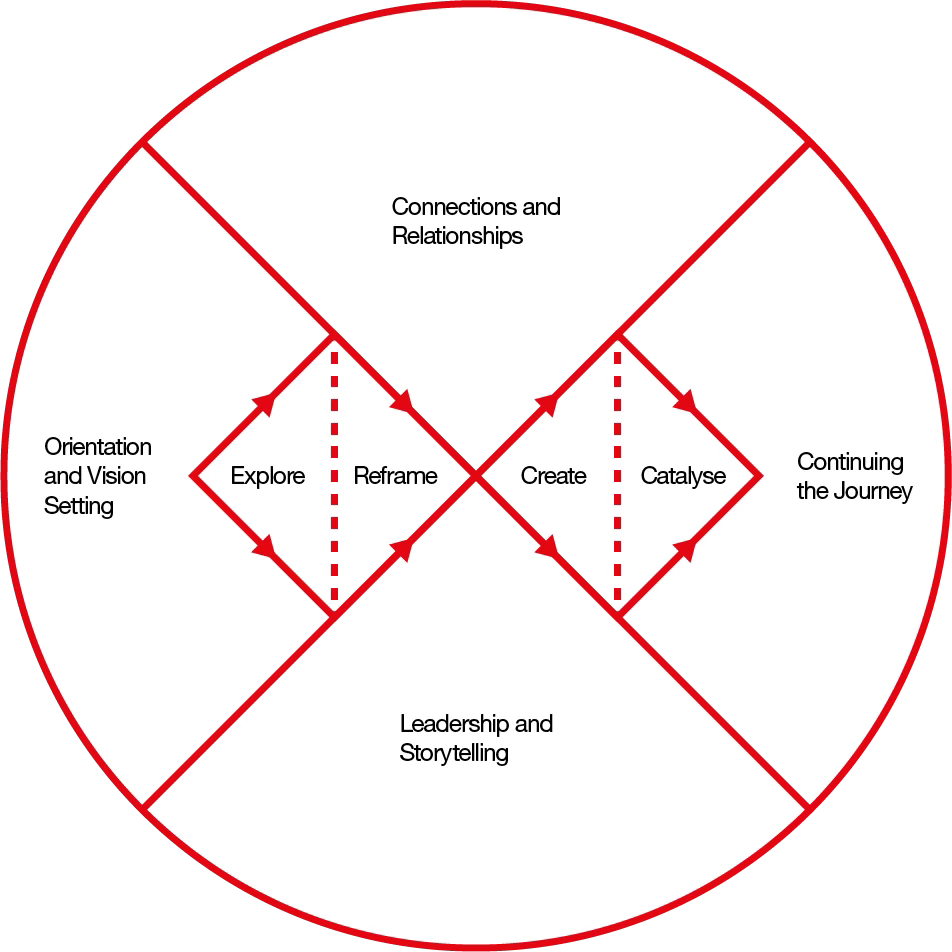

An alternative worldview considers design value through a systemic lens that privileges societal and environmental health. The Design Council introduced the Systemic Design Framework in 2021, as an evolution of the original “double diamond.”

From their website:

Systemic design is the acknowledgement of complexity and interconnectedness throughout the design thinking and doing process. It is both a mindset and a methodology - considering the structures and beliefs that underpin a challenge.

It asks both designers and non-designers to radically reimagine and create new ways of living.

The climate and biodiversity crises, and associated social injustice, are the biggest challenges facing humanity today, and so design must evolve to include these: acting more systemically, shifting towards alternative regenerative systems. (Design Council, 2025)

The Systemic Design Framework (2021). Two diamonds are better than one.

The aims of regenerative design are not inherently at odds with business, though the mindset shift requires that businesses and capital reconsider growth as the primary metric.

Consider how that might also change the relationship between design and business—where the former need not justify its role within the current system.

Might we someday speak of the design value of business rather than the business value of design?

The Big Question

Can a new future of design transcend its origin in modernity?

Endnote

Back to Papanek. If the clock was at one minute before twelve in 1971, I imagine there are only seconds left today, if that. He calls on designers to exercise moral agency—a challenging task within powerful structures designed to minimize it.

Still, design needs to rise to the occasion.

A way to evolve the system at the worldview level would be to acknowledge the differing value systems of business and design and identify areas of shared interest and leverage—as well as trade-offs. This sort of synthesis could catalyze and scale the regenerative solutions we urgently need.

References

Papanek, V. J. (1971). Design for the real world : human ecology and social change.

Design Council Systemic Design Framework

McKinsey Business Value of Design

On the cover: Dieter Rams, Ten Principles of Good Design