Alternative Hedonism

Kate Soper’s Post-Growth Living as a radically optimistic image of the future

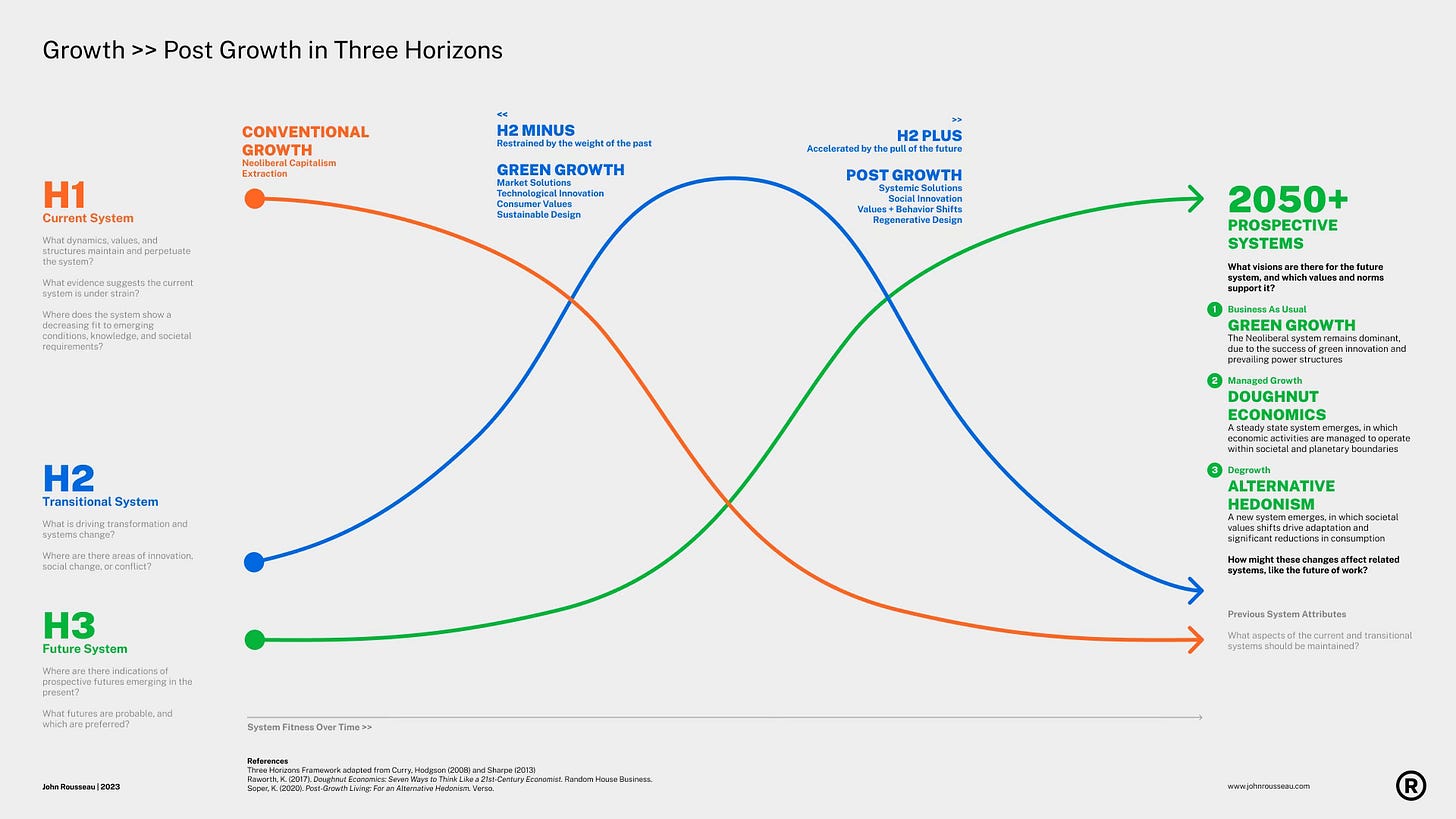

Amidst worsening climate forecasts, missed decarbonization goals, increasing economic dysfunction, and generational change, post-growth seems to be having a moment.

Whether calling for managed, low-growth economics or more aggressive degrowth, post-growth theories share a common critique of neoliberal capitalism and by extension the green growth agenda: namely, that any system based on artificial scarcity, perpetual economic growth, and sustained or increasing consumption is destined for planetary overshoot and systemic collapse, regardless of whether it is feasible to decarbonize global energy, decouple emissions from GDP, and reach net zero by 2050.

These ideas also assume that the sort of changes in growth and consumption required to bring the economic system within societal and planetary boundaries will necessitate significant values shifts, consumer behavior change, and lifestyle adjustments in rich countries, amidst prospective social turbulence and economic uncertainty. This makes the post-growth vision a hard sell politically, especially compared to a green growth future that promises market-driven technological innovation and progress, top-down solutions, and a painless continuation of the status quo.

In Post-Growth Living, For an Alternative Hedonism, Kate Soper reframes the post-growth narrative in terms of what might be gained rather than what would be sacrificed. Soper argues for an alternative hedonism that represents an expansive vision of prosperity based on liberation from the work and spend cycle that is endemic to capitalism. She writes:

Unlike the more alarmist responses to climate change, alternative hedonism dwells on the pleasures to be gained by adopting a less high-speed, consumption-oriented way of living. Instead of presaging gloom and doom for the future, it points to the ugly, puritanical and self-denying aspects of the high-carbon lifestyle in the present. Climate change may threaten existing habits, but it can also encourage us to envision and adopt more environmentally benign and personally gratifying ways of living.

Alternative hedonism is premised, in fact, on the idea that even if the consumerist lifestyle were indefinitely sustainable it would not enhance human happiness and well-being beyond a certain point already reached by many. Its advocates believe that new forms of desire—rather than fears of ecological disaster—are more likely to encourage sustainable modes of consuming. (Soper, 2020)

Soper imagines a dialectical theory of change, where a post-growth alternative to the dominant worldview could drive the emergence of a new, post-capitalist system. Specifically, she argues that shifts in values among the polity can drive changes in policy through collective action, and vice versa—that proactive changes in policy can create greater acceptance of new ideas, lead to new behaviors, and so on, as part of a virtuous cycle.

Put another way, changes in thinking drive changes in behavior, which drive changes in thinking.

This sort of top-down and bottom-up framing is notably absent within mainstream climate discourse, which focuses on corporate action (or inaction), the relative ineffectiveness of policy makers, and the frustrating disinterest of the public in holding either to account. This is partly a feature of the dominant capitalist episteme and incentive structure, and partly a determined reluctance to locate genuine agency or responsibility across all levels of the system, specifically including individual consumers and citizens (e.g., we “fight climate change” as a systemic abstraction or technical problem rather than reflect on the impact of our own behaviors and values).

Soper writes:

The politics of prosperity that we need today must dissociate pleasure and fulfillment from intensive consumption, from the endless accumulation of new machines and gadgetry, from tourist space travel and the like, and from so much else based on unworkable assumptions about what would constitute globally sustainable modes of life. In this context, eco-socialists and Marxists must press for a debate on the good life, and argue the need for the Labour movement to reframe their short term economic goals and environmental policies in ways consistent in the longer term with a vision for the future of work, consumption, and human satisfaction no longer dependent on continuous growth. (Soper, 2020)

So what is the good life, and who decides? What is a truly revolutionary, long-term vision for the future of work and pleasure?

In 1930, John Maynard Keynes predicted that by 2030 we would be working fewer than fifteen hours a week, and that the extra time would allow society to pursue more intrinsic goals. Instead, productivity gains over the past century have turned into more time working and considerably more stuff.

Looking ahead, Soper contrasts the familiar “technological-utopian” vision with alternative hedonism. In the technological-utopian view (i.e., green growth), the future of work is more productive due to technological innovation, less laborious due to automation, and more green due to clean energy—though pleasure is still derived from an increasing abundance of consumer goods and services, even in the event that less labor is needed. It’s business as usual.

The alternative hedonist view is more agnostic about technological progress and emphasizes purposeful work—in particular the sort of labor that is socially valuable and individually meaningful but poorly compensated (e.g, caregiving, growing and preparing food, conservation, craft, teaching, etc.). Soper argues that rather than automating or outsourcing these sorts of routine tasks, they may turn out to be truly enjoyable and deeply rewarding, particularly in service of others.

Soper doesn’t build out this vision in great detail—her argument is more polemic than plan, and in those terms I think this is a valuable book. I appreciate the focused critique of contemporary capitalism and the way alternative hedonism provides a radically optimistic and more just image of the future that also happens to be much better for the planet.

And that clever inversion is what makes it appealing, particularly when imagining the sort of collective action that will be required to inspire systemic change.

A Post-Growth Reading List

Hickel, J. (2020). Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World. Random House.

Jackson, T. (2016). Prosperity without Growth: Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow. Routledge.

Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. Random House Business.

Soper, K. (2020). Post-Growth Living: For an Alternative Hedonism. Verso.

I liked this a lot. I think of the grain farmers I heard talk last week at Oxbow (one farms in the Skagit Valley, the other on the Olympic Peninsula) and the beautiful produce I saw today at the Ballard Farmers Market. I know a lot of small food producers are already pursuing their own visions of alternative hedonism. It's so inspiring to hear them talk about it.